Immortality: The Gift of Portraiture by Dinah Hulet

An interview by

Shawn Waggoner

Glass Art Magazine

Sept/Oct, 2000

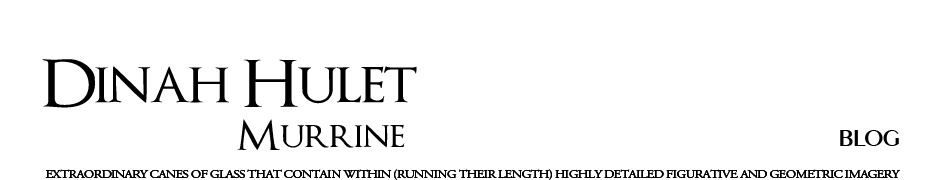

Like the Alexandrian glass of ancient Egypt, the glass treasures of Dinah Hulet will eventually be discovered. Hulet has mastered techniques developed between the 1st Century BC and the 1st Century AD, around the year one. During this period one of Egypt's major exports was glassware, and Alexandria was famous for its manufacture of elaborate, expensive glass aimed at the upper class market in Rome and elsewhere. The most desirable type of Alexandrian glass was made up of what we now call millifiore or murrine, segments of patterned glass sliced off of a pre-made glass rod or cane. The technique of combining simple elements to make a complex design is called "mosaic glass", Hulet's specialty. The artist began making glass face canes in 1992, which she used in marbles and beads. But a call from Hulet's mentor inspired and challenged her to push her technical abilities and aesthetic approach to a new level. In 1996, after a year of experimentation, Hulet had created a detailed portrait cane of Paul Stankard, a turning point in her career. Currently the artist is working on a larger scale. She makes glass "cubes", which measure 1.25" high, 1" wide and 1.5" deep. She doesn't stretch the cubes as with traditional canework, because she wanted to expand the size of her image. Instead, Hulet assembles the cubes at nearly full size to create a portrait in glass which captures all the emotion, life and mystery of the human face. Her piece, "Into My Life There Came a Man Named George", represented a leap forward in her work and, more importantly, inspired a new level of intimacy between viewer and subject. In June, Hulet presented slides and a lecture on her work at the Glass Art Society conference held in Brooklyn, New York. She has instructed at UrbanGlass, Brooklyn, New York, Penland School of Crafts, Asheville, North Carolina, and at various other conferences on paperweights, beads and marbles. Her work appeared in New Glass Review 20, the Corning Museum of Glass publication, and can be found in the permanent collections of The Bead Museum, William Warmus, The Corning Museum of Glass, Robert Liu and Paul Stankard. In the following conversation with Glass Art magazine, Hulet

discusses her technical and aesthetic approach to mosaic glass,

and the evolution of her work into its current portrait form.

GA: What is the appeal of the portrait to you? I provide the face - you provide the story to go with it. GA: You have master's degrees in both music and library science. How and when did you begin working with glass? DH: I was on the faculty at the University of Idaho as a humanities for a year until I realized that wasn't what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I quit and moved to Denver where my boyfriend Rob was a chemist at a rubber company. He had gone to Georgia Tech when Godo Fräbel was a scientific glassblower there. Inspired by what Fräbel was doing, Rob set up a torch, and eventually I started experimenting with it too. Once I started selling some of my glasswork, I never went back to the real world. I was in Denver for about 12 years where we had a small gallery. In 1984, I took my daughter and moved to California where my sister Patty was raising her daughter in the San Francisco Bay Area. I moved in with her, and one day when I was doing glasswork in the garage, I told her, why don't you quit your job (she was a medical administrator), and let's go someplace really nice and just do glass. She surprised me when she said, "OK". We moved up to where we are now, on the north coast, right on the ocean. We've been working on glass and raising our kids here ever since. Patty does some of the production work, all of the business

functions and all of our photography. She allows me the time

to work on the canes. GA: What was your work like in the early days? GA: When did you first become interested in historical

murrine and millifiore?

In 1995, I decided to attempt a detailed portrait cane in the manner of Giacomo Franchini's incredible miniatures using Paul Stankard as my subject. In the middle of the 1800's in Venice, Franchini, a beadmaker, began creating mosaic glass imagery in the manner of the Ancient Egyptians. It had taken only 1,800-plus years for this technique to be re-discovered. He created a cane of a rosebud by starting with a simple design and adding additional details to it to build a more complex cane. He then went on to create a series of seven incredibly detailed miniature mosaic glass portrait canes of contemporary Italian political figures. His portrait of Count Cavour is about 1" in diameter. After completing his last portrait, one of the Emperor Franz Joseph, Franchini was placed in an insane asylum, where he died, and the secrets of how he created his amazing portraits died with him. When I began to make my first portrait cane, little did I realize the difficulties and frustrations I would encounter. I spent countless hours developing a palette of colors, having to mix glasses to arrive at an adequate range of skin tones, and then I had to determine a method of attack. Like the ancient Egyptians and Franchini, I made separate canes for each feature. I then combined them in stages adding hot glass as I worked to build the shading and the form of the face. Slowly, after many, many failures, the face emerged, and after a full year of working on the project I placed the finished portrait in Paul's hand.

I followed up the Stankard piece with several more small portraits.

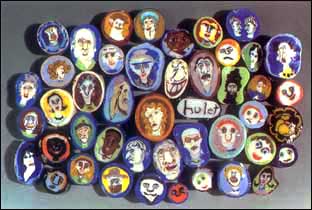

As I was working on these portrait canes I became interested

in creating "lover's eyes", based on the miniature

paintings of eyes derived from the portrait miniatures that were

popular in the early part of the 19th century. Portrait miniatures

were the snapshots of the day - they were small portraits usually

painted on ivory intended to be carried around when one traveled

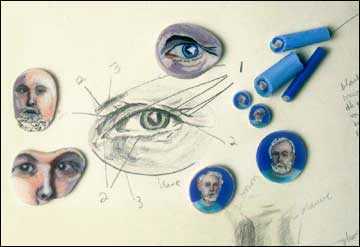

or to be worn as broaches or pins. GA: How did this work evolve into your current process? Continuing with the idea of using multiple slices taken from a single mosaic glass cane, I did a portrait study using repeated imagery. I then took the concept another step further with a geometric piece, where I mounted multiple triangle-shaped cane slices to create the illusion of depth.

And then it occurred to me - I was using this mosaic glass

technique in the manner of glass mosaics, where separate pieces

of glass (called tesserae) are arranged so that they build an

image. I was not only combining separate elements to make a complex

design within a single cane of glass -- I was then combining

these complex cane slices to form another, larger, even more

complex design. This realization caused me to completely rethink

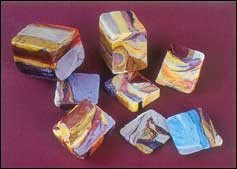

the work I had been doing. GA: Can you describe your process? I then set about building a series of preplanned rectangular canes or more accurately "cubes". Before I start, I come up with a palette of colors, mix them and pull my canes. I label the colors to correspond to a master sheet. I work more from the reference sheet rather than depending on what I'm looking at. Many times when I mix colors, I don't know what the color is going to look like once it's inside the cane and has been annealed and sliced.

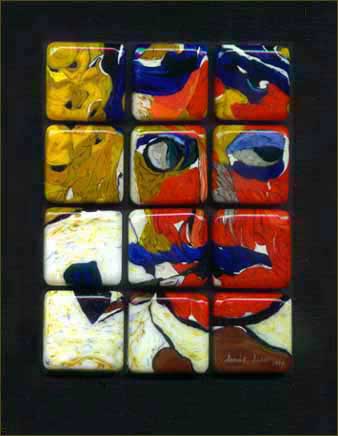

As I build these cubes at the torch, I cannot see the detail of line, color and form that I'm sculpting three-dimensionally within each of them. It is only after the glass is annealed, when I slice into the cube, that the imagery I constructed on the inside is revealed. Remember the image is inside the glass, not on the surface. I don't stretch the glass cubes down to a smaller size because my intent is to expand the size of my image - not to miniaturize it. I refer back to my paper rectangle to see if I got what I wanted. Sometimes I have to do as many as five different versions to get exactly what I'm looking for. It's not until I have all the pieces lampworked, sliced and laid out that I see the actual image of the face. The sliced cubes are adhered to a base frame with silicon adhesive. I want space between each of the rectangles in the grid so the viewer can see the sides of the canes, because there's imagery there, too.

A fiction author shows you his characters through the use of words, and then it is up to the reader to visualize how they look. I am presenting the viewer with a visual image, and the viewer can come up with the words to describe the character he/she sees. I have my story (a very interesting one) - what is yours? I followed up "George" with Lynn: Image/Self-Image", using as my subject a combination of the faces of my mother and my daughter. I limited myself to a palette of blues and black in order to set a mood and to develop a tone-poem in glass.

Let's look back again at ancient Egypt, to the 1st and 2nd century AD, and to a location south of Alexandria -- to the Fayum. The Fayum, one of the richest and most important provinces of Egypt, was a very lush agricultural region only about 150 miles south of Alexandria. Large quantities of grain and papyrus were produced there, and then sent by boat up the Nile to Alexandria and exported on to the entire Roman Empire. Various goods were then brought back from Alexandria to the Fayum area. Among these goods was glass -- indeed at one archeological site in the Fayum there was discovered over twice as much glassware as has been found at any other single site in Egypt. Another very significant archeological discovery of this period, and located primarily in the Fayum region, are the famous mummy portraits. A major exhibition of mummy portraits closed in May at the Metropolitan Museum. These wonderful mummy portraits were painted in tempera or wax on canvas or on thin wooden panels that were then mounted over the face of the mummy. It is believed that these portraits represent the Egyptian elite -- those who could afford to have their portraits painted and their bodies mummified after their death, and those who were most likely to have had beautiful Alexandrian glass in their homes. Remember, this was during the time of the initial development of glassblowing. Just think, these were most probably lips that drank from some of the earliest blown glass vessels. These wealthy citizens would also most likely have been early collectors and patrons of mosaic glass that was used as decorative inlay in their furniture and wall pieces. I decided to select from among the more than 100 ancient mummy portraits, two as models for my newest portrait. It's difficult, without the class distinctions of clothing, jewelry and hairstyles, to distinguish the faces of these affluent Egyptians from the Alexandrian glassworkers. I created a double portrait of two fictional ancient Alexandrian glassworkers -- one, who, like me, created time-consuming, labor-intensive mosaic glass, and the other, who was captivated by the newer, exciting and much more immediate technique of blown glass, a development that contributed to the loss of the older mosaic glass technique.

With this work I encourage artists to do whatever they can to nudge the boundaries of glassworking outward and to further expand the possibilities of what can be created out of this remarkable substance we call glass.

|

|---|